When Truth Becomes Optional: Thoughts by Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt once wrote, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction and the distinction between true and false no longer exist.”

DEMOCRACYCULTUREPOLITICS

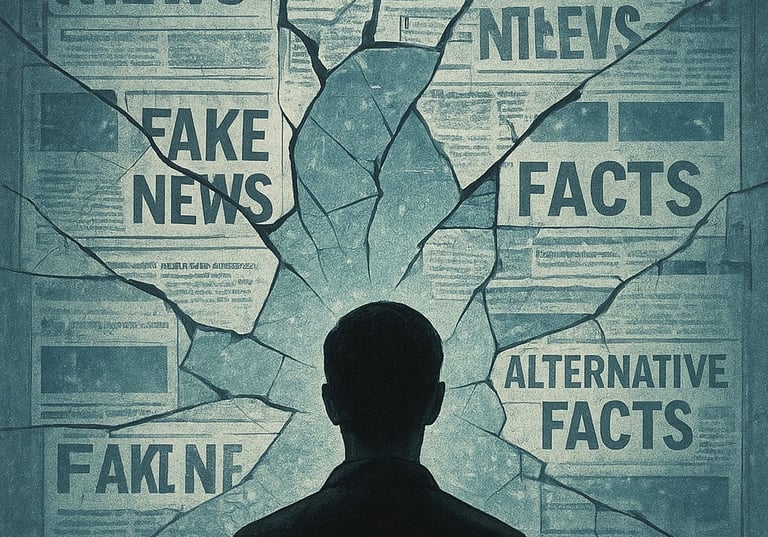

The Erosion of Truth

Hannah Arendt once wrote, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction and the distinction between true and false no longer exist.”

She wasn’t describing blind loyalty so much as moral and intellectual collapse. Totalitarianism thrives not on conviction, but on confusion—on citizens so overwhelmed by competing claims that they give up on distinguishing truth from lies. Once that happens, reality itself becomes pliable, something that can be molded by whoever holds the most power or controls the loudest microphone.

It’s not the loyal ideologues who make a totalitarian system possible; it’s the millions who shrug and say, “Who can really know what’s true anymore?” When a society reaches that point, propaganda doesn’t have to convince anyone—it just has to exhaust them. People stop asking for evidence. They stop caring about consistency. They stop expecting truth to mean anything at all.

The Age of Confusion

Arendt saw this in the aftermath of the 20th century’s great dictatorships, but her words echo with eerie familiarity today. We live in a time when information is infinite but trust is scarce. Disinformation spreads faster than facts. Entire media ecosystems exist not to inform, but to reinforce feelings. Truth has been repackaged as a matter of personal preference, and every opinion now comes with its own “alternative facts.”

In this landscape, propaganda doesn’t arrive wearing a uniform—it arrives in our newsfeeds. It flatters our biases, confirms our resentments, and teaches us to distrust everyone outside our tribe. The danger isn’t that people will believe one specific lie—it’s that they’ll stop believing there’s any difference between truth and falsehood at all. Once that line disappears, anything becomes possible.

The Political Cost of Disbelief

And that’s where the political danger lies today. When citizens are untethered from reality, democracy becomes impossible to sustain. How do you debate policy or hold leaders accountable when you can’t even agree on what’s real?

We see it in a movement that calls verified journalism “fake news” while treating obvious falsehoods as sacred truth. We see it in politicians who lie with impunity because they know their supporters no longer care. The collapse of truth is not a side effect of authoritarianism—it is the precondition for it.

The most dangerous weapon in politics today isn’t a gun or a law—it’s the erosion of reality. If enough people decide that truth doesn’t matter, then power becomes the only thing that does. And once that happens, the slide from democracy to something darker won’t come with a bang; it will come quietly, disguised as apathy.

The Final Warning

If Arendt were alive today, she might remind us that defending truth isn’t an academic exercise—it’s an act of resistance. A functioning democracy depends on citizens who still care about what’s real, who refuse to surrender to cynicism or fatigue.

Because when truth becomes optional, freedom becomes temporary.

AI Generated image